Location map of the historic Khlong Ong Ang Community and Saphan Han area

1. The birth of Saphan Han

We need to grab the dragon by its tail, or else he’ll be gone.” Mr. Suwat is concerned that the Khlong Ong Ang community will miss out on a great opportunity. His community is located on the western end of Bangkok’s Chinatown and is named after the old moat that served as the lifeline for this micro neighbourhood.

Khlong means canal and Ong Ang refers to the earthen wares that were sold here over a century ago. The canal saw transitions from a militarised buffer zone to Bangkok’s newest award-winning tourism development project: The Saphan Han Walking Street. Saphan Han means swivel bridge and his a historic landmark that spans across the canal. The new promenade along the canal is the embodiment of Bangkok’s economic vitality and an example of megacities and their stories of transformation. We take a closer look of the impact of the new attraction, what it offers and the hopes and aspirations of those living at this historic landmark.

Ancient Daoist belief. A mystical lion protects the homes of residents in the Khlong Ong Ang Community

Chinese roofs. The ancient homes of wealthy merchants who built the Saphan Han Community during the early days

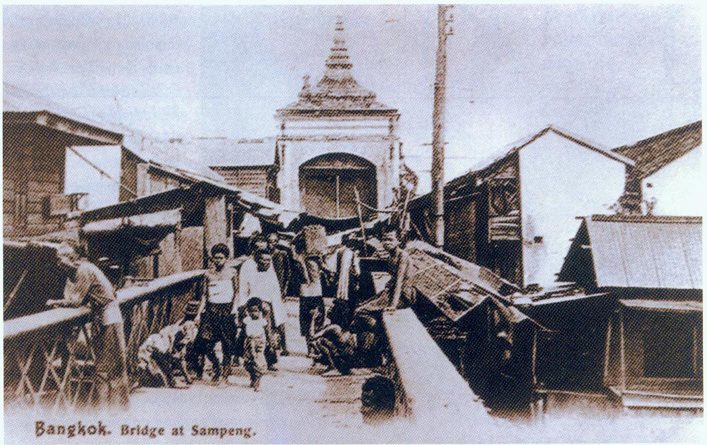

The story of Khlong Ong Ang is also the story of the founding of Bangkok. The canal marked the fault line between the Chinese settlement of Sampeng and the sacred palace area. Constructed to keep enemies out and yet retain a fragile link to the Chinese periphery through a flimsy wooden bridge that swung to either side as boats passed. Hence the name Saphan Han (Swivel bridge).

Mr. Suwat is belongs to Chinese Teochew ethnicity, a Chinese dialect group from the southeastern prefecture of Chaozhou. His ancestors along with an estimated 15,000 Teochew (*1) settlers were forced to settle outside the fortified city walls in the marshy tracts of Sampeng. (*2) to make way for the construction of the Grand Palace. A year later the King completed the excavation of the Khlong Ong Ang canal and complete with a city wall, fortifications and a militarised buffer zone created the bulwark against foreign enemies or potential Teochew uprisings.

1* Teochew: Thailand’s main Chinese ethnicity and one of five Chinese speech groups in Thailand. 2* Sampeng: The first main street (alley) of Chinatown and core of the Chinese settlement in Bangkok). 3* Thonburi: The old kingdom and capital (1767 – 1782) before the founding of Bangkok, located on the western side of the river.

The Saphan bridge underwent several reconstructions. View across Saphan Han bridge toward the city gate in mid to late 19th century

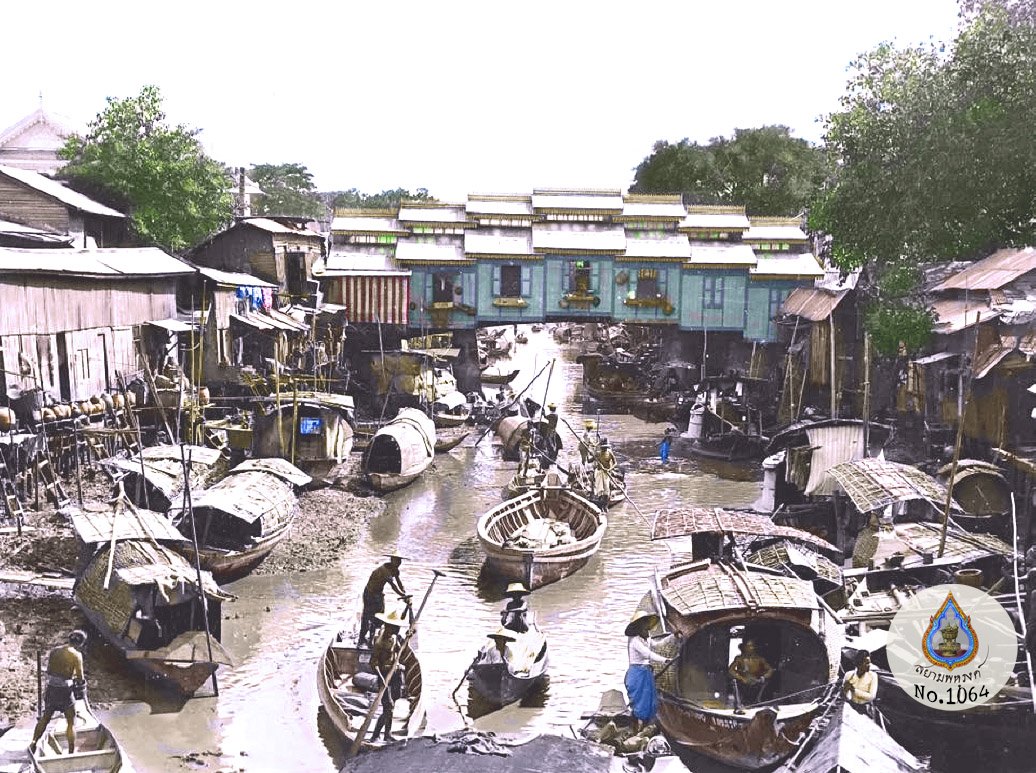

Chinese architecture dominating the banks along Khlong Ong Ang in the old days. The area next to Saphan Han could be a city in southern China.

2. Italy in Chinatown, the first great transformation

During the reign of King Chulalongkorn (1868 – 1910), the priority of self-defence and the suspicion of an uprising had shifted to what really mattered – doing business. As Chinatown expanded and Khlong Ong Ang became a thriving market centre, Saphan Han became the busiest transit point between the port and the palace district. With the growth came environmental problems. The canal became heavily polluted and silted. This prompted a major overhaul, including a complete new look for Saphan Han.

It was also the end of an era in which Bangkok was predominantly water-borne, relying on a vast network of canals for living, commerce and transport. Through King Chulalongkorn’s Western oriented policies and a growing foreign community, Bangkok shifted from a water-based towards a land-based city. Throughout his reign the construction of countless roads and bridges ensued and so did Saphan receive a worthy bridge of its own.

It became the area’s historic memory and symbol however it was not a bridge crowned with a Chinese pagoda or a design in honour of Mount Meru but a Souvenir King Chulalongkorn (King Rama V) brought back from his trip to Europe.

Western style gentrification made inroads into Bangkok with the arrival of the Western free market ideology and growing pressure from Western empires. During his visit to Europe in the 1890’s, the King had cast iron frames prefabricated in Italy, then imported and installed by Italian architects to turn Saphan Han into the little brother of the Ponte di Rialto in Venice.

Saphan Han in the late 19th century. The flagrance of Italy in Bangkok’s Chinese commercial quarters

Saphan Han, seen in the community’s art display

3. The great neglect – Bye bye Venice of the East

There is a book title called: ‘The cars that ate Bangkok’. It’s quite descriptive of what happened in Bangkok from the 1960’s onward, the complete dominance of cars and road infrastructure and an appealing treatment of Bangkok’s waterways. On top of that, rapid and uncontrolled urban growth saw much of the city’s vernacular heritage being destroyed including the Italian version of Saphan Han which was replaced in 1962 with the wider and reinforced concrete structure of today. International tourism and floating markets kept the image of an aquatic society somewhat artificially alive as the role of canals further decline toward the end of the century.

Saphan Han and Saphan Lek are land based markets. The former became famous as a textile market the latter was known as a hub for toys, video games and electronics. Both markets were located along and on top a historic canal and had identically named historic communities. Aside from historians, this completely escaped people’s knowledge.

Inside the historic community of Khlong Ong Ang

Vanishing heritage. Entry gate of an ancient Chinese homes along the canal. Bangkok has been losing it fascinating architectural heritage for many decades.

What’s left of urban villages around Khlong Ong Ang?

Wider neighbourhoods such as Saphan Han are often associated with specific products or industries. In these areas we can find smaller, specialised micro-communities. They can be rooted in crafts, clan affiliation, religion or ethnicity. As with the role of Bangkok’s waterway so did the importance and function of urban communities decline. Saphan Han is still to a large extend run by the descendants of Teochew immigrants as is the rest of Sampeng. Businesses changed hand from one generation to the next but with the developments occurring in surrounding neighbourhoods it begs the question whether this is going to continue?

Into the intricate fabric of urban communities

Workshops of gold smiths and jewellery smiths can still be found in those micro-villages

We are entering a forgotten world. Craftsmen and local aunties are going about their daily chores in a warren of brick walls, fainted and crumbling plaster, timber structures, laundry, Daoist symbols, electric cables and the smell of home-cooked food. It’s hard to tell where a community ends and where one begins. My guests usually find themselves in puzzled amazement about the intricacy of this urban web. Traders and craftsmen lived and worked in micro-communities such as Trok Hua Met which fused into the area of Saphan Han. Those names still evoke memories of the jewellery and gold smiths that had traditionally been located here but had to relocated in the wake of urban development in the 1980’s. You can still find a craftsmen such as Pee Noy who learnt the craftsmanship as a young apprentices from the area’s original masters.

Pee Noy, carrying on the legacy.

The community leader

There are 18 communities left in Bangkok’s Chinatown represented by community leaders of a total of more than 2,100 urban communities of which 140 are classified as historic communities according to the National Housing Authority. Each community has a community leader who functions as the voice of the people like Mrs. Nattawan nickname: Aum, the community leader of Khlong Ong Ang. Her ancestors arrived from China by junk and were able to set up shop on the Saphan Han bridge back when it was still the Italian version. Pee (*1) Aum has continued the business of her family and is determined to develop and lead her community into the future.

Pee Aum, the communiy leader of the Khlong Ong Ang community. “In the past, visitor didn’t even know they were in Saphan Han because they couldn’t see the bridge or the bridge for all the shops and structures blocking the view.”

Khlong Ong Ang in 2015 – The wild side of Bangkok

Khlong Ong Ang was excavated for defence reasons but it also held spiritual symbolic meaning. Like other canals it was excavated in a concentric pattern around the city’s founding pillar adjacent to the royal palace. The ancient, concentric layout of Bangkok aligned with Hindu Cosmology as a means of protecting the sacred Mount Meru, the centre of the universe or the divine capital in which the King and guardian spirits resided. Given its rich history, the canal was registered as a historical landmark with the Fine Arts Department in the 1970’s.

Passing through Trok Hua Met and the Saphan Han in 2015, you could barely notice the existence of this canal, let alone grasp its cosmological functionality. Only by crossing one of the steel bridges you’d notice the canal. It was an ignored relict of the past and a place to spot ‘pre-historic’ animals such as giant monitor lizards, turtles and massive pythons. Guests were usually at awe with the urban jungle.

Excavated in 1783, one of Bangkok’s oldest moats, dating back to the beginnings of Bangkok. After decades of neglect, the historic moat Khlong Ong Ang turned into a mini version of the Amazon complete with encroaching makeshift structures serving local businesses and the market. This image was taken in 2014.

Saphan Lek Market covering the Khlong Ong Ang canal north of the bridge. Saphan Han market along Khlong Ong Ang south of the bridge. Photo credit: Thairath newspaper.

It was hard to fathom such a jungle exists in the middle of the city. This is how the world emerges if it’s left on its own for decades. The veil of time has its own aesthetics. For some people, all they see is urban decay. For me these are the organic layers of time that linger over Bangkok’s forgotten past. Urban exploration gave me the opportunity to lift the veil of obscurity and uncover Bangkok’s hidden communities. Saphan Han and the surrounding area in the early 2000’s were the epitome of the unruly yet mystical Bangkok.

Pee Aum still can’t fathom the change. “When people visited Saphan Han, they didn’t even realize they were in Saphan Han because you couldn’t see the bridge. All the shops, crowds, plastic awnings, storage, kitchens and food stalls blocked the view even of the sky.” She’s amazed and glad that I kept some pictures of the area. People are often too busy or accustomed to their surroundings and do not have the same sense of urgency to keep photographs. I’m glad I did but I still regret that I began late.

Bangkok’s underground Toy’R’us

Exploring the world of informal markets of Khlong Ong Ang while being oblivious of the existence of Khlong Ong Ang.

Saphan Han and Saphan Lek almost seamlessly connected. You crossed Yaowarat road and entered the Saphan Lek market below the bridge. It felt as if you were swallowed into a bladerunner style underground market. A semi-legal microcosm that consisted of nearly 500 shops sitting along and on top of the canal. It was the cyberpunk version of Toys R Us and the go-to place for boys and grown men to buy game consoles, Playstations, BB-guns, drones, anime figures and other toys. That was until 2015, when the marked was evicted and the 275 million baht facelift began.

Excited travellers exploring the world of informal markets. Some even bought an old classic NES. The good old days.

4. The great urban renewal – Is our Chinatown gone?

Pee Aum was one of nearly a thousand businesses impacted by the urban renewal project. People weren’t given much advance notice. Sixteens days to be exact. We weren’t sure about the future. We have been trading in our spaces since our grandparents and now? Those live in the community were the lucky ones. They continued working from their homes. Others less fortunate had to move on.

The eviction came in tandem with another massive eviction ; the redevelopment of the neighbouring Woeng Nakhon Kasem Community. An entire neighbourhood switched hands for 4.6 billion baht. Like many properties it is now owned by Thailand’s second richest Tycoon Mr. Charoen. (Owner of the Chang Beer brand). This development project seemed very well choreographed with the private sector who is going to develop Woeng Nakhon Kasem into something new but it’s still a question mark what will replace this once thriving neighborhood and what this will mean for the communities down at Saphan Han.

Uprooting the urban jungle. Radical facelift and sixteen days notice. Change came fast. Change is the only constant in life.

Top-down or bottom up development?

People are concerned that these developments could spell the end for Khlong Ong Ang’s historic communities. The track record of urban development under the leadership of bureaucrats shows that heritage preservation is an uphill battle. The city’s campaign against the informal nature of Bangkok wiped off entire street markets, street food vendors and did not even stop when it comes Bangkok’s oldest communities which are deemed encroaching slums. The government has its reasoning behind it but the results we saw with our own eyes were that popular and vibrant streets turned into “dead-zones”and unique historic villages into what looked like a mini-golf course. Hence our concerns for Khlong Ong Ang were justified. But will this actually be the case?

From the epitome of chaos to a green open space in Chinatown. After a lot of scepticism the people started to warm up to their new environment especially after the opening of the Saphan Han Walking Street.

So far, the signs are positive. The government has shown a shift from the top-down handling of development toward a more participatory approach. Pee Aum and the residents of Khlong Ong Ang met with city officials to discuss the desire to set up a market along the canal which was eventually approved. Spaces for selling were free and even the electric costs for the light installations were waived during the first three months. This fills people with hope that the new promenade can develop in a way that benefits the local economy.

Art plays an important role to attract visitors from other parts of Bangkok

5. The future and why you should visit Khlong Ong Ang and Saphan Han

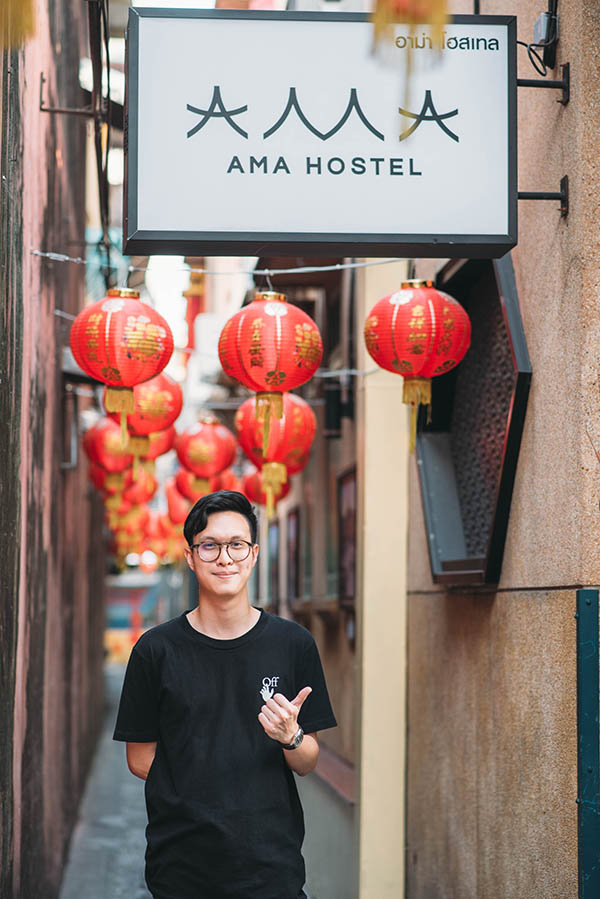

“After the eviction and clearance we began to notice how beautiful our community actually is. We want to share this beauty with the world” says Pee Aum. For years the landscape improvements didn’t bring any real economic benefits for the people. “Everyone would go home by 5:00p.m. Then it would be dark and quiet” says Moss who converted an ancient Chinese house into Ama Hostel, the community’s first hostel. Moss’s family like many in the Saphan Han area run a textile business. The 200 year old building was used as a storage facility but after graduating entrusted the building to him to accomplish his dream of running a hostel.

Could the concept and philosophy Ama Hostel could be applied as a strategy of the entire neighbourhood? To preserve the old by blending it with the new?

Moss the illuminator

Mixing old and new

After five years of hibernation, Khlong Ong Ang is finally waking up. Singapore has Marina Bay, Shanghai has the bund and Bangkok has the Saphan Han Promenade. Well, maybe the comparison is not valid as the businesses here are in line with Bangkok’s popular street economy consisting of mostly small vendors, booths and small no-frills restaurants. The lower half of the walking street is actually a living community. It’s the people that inject the life, feel and character to the place instead of international brands or upscale restaurants.

But the opportunities are here. People from near and far flog to the new promenade for photos, kayaking, food and relaxation. The upper half of the promenade near the Samyod MRT Station has most of the street art. The westside on the lower half boasts numerous Indian restaurants while the Chinatown side offers Teochew classics among other delicacies.

Trust levels in the water quality are at an all time high since King Rama V. People paddling kayaks without fear of falling into the water and morphing into the next Batman villain.

While strolling along the canal, many people are drawn by some beautiful light emanating from deep inside an alley. There’s more to the area than only the canal. The alley in question is called Trok Ama, the one named after and leading to Moss’s hostel which also offers a small yard and cafe. The generation of Pee Aum’s parents referred to the alley as Soi Kee Ma: Dog poop alley and would avoid it but now it has become one of the community’s highlights. Moss lit the entire alley with Chinese lanterns which adds to the atmosphere in the evenings. Nearby, a young female entrepreneur offers high-quality tea inspired from Taiwan at Ing’s teahouse. The new generation is adding their flavour to the neighbourhood and it costs a fraction of what people pay in shopping malls.

The Chinese legacies of the community

Seeing the popularity of the community’s old character Pee Aum regrets that they haven’t kept any pictures of the old magnificent buildings. The houses, gates and trees were once the charm of the community. But some of it is still there and Pee Aum hopes the community will preserve the old rather than demolish it. I think people come to realise that the old highly valuable and they want to keep it. The community has still retained a lot of its old architecture and visitors enjoy a slight sense of adventure when exploring the alleys. The old brick walls, the organic patterns, tones and colours of old buildings stand in a stark contrasts to Bangkok’s embrace to the modern, glitzy hangouts in downtown.

Steering historic communities toward the future in times of rapid urban change

Trok Ama is proof of what Bangkokioans cherish and that is has overall benefits for the entire community. Pee Aum has more plans and her plans take the 300 families into account that consists mostly of elderly. Pee Aum would like to install lights in the community’s alleys. Beautifying the community in a gentle way would allow the elderly to work from their homes. She drew the inspiration from the historic market in Chiang Khan, a city in the north of Thailand. It would develop local tourism and elevate the beauty of the physical heritage and help the community to earn enough and hopefully attract the younger generation to return to their roots.

Building resilience and opportunity for the elderly

Mr. Suwat believes the dragon is back. “If we don’t seize the opportunity the dragon will be gone, we need to catch the dragon!” But who will catch the dragon? The Chang Beer tycoon is rumoured to be negotiating the acquisition of more properties nearby. The community leader is confident that they will not be driven out by investors. “We grew up here, we are rooted here and we’re a tight knit community. We’re not going anywhere. The businesses here continue on from one generation to the next. The culture and traditions are still intact.”

If the creativity of young entrepreneurs, the experience of business people like Mr. Suwat and the leadership of Pee Aum can be synchronised to strengthen, innovate and share the unique heritage of Khlong Ong Ang, the role of historic communities can be elevated and ownership remain in local hands. It would benefit local economies, enhance Bangkok as a cultural destination and bring happiness for locals and travellers alike.

If you agree, feel free to share this article with your friends or anyone planning to visit Bangkok and with a heart for culture, people and heritage. Thank you